The road to recovery

The Gordon Moody Centre in Dudley, West Midlands provides a residential rehabilitation program to former gambling addicts. Some of the centre's former residents speak to Daniel O'Boyle about how the Gordon Moody Assocation (GMA) has helped their journeys to recovery.

The Gordon Moody Centre in Dudley, West Midlands provides a residential rehabilitation program to former gambling addicts. Some of the centre's former residents speak to Daniel O'Boyle about how the Gordon Moody Assocation has helped their journeys to recovery.

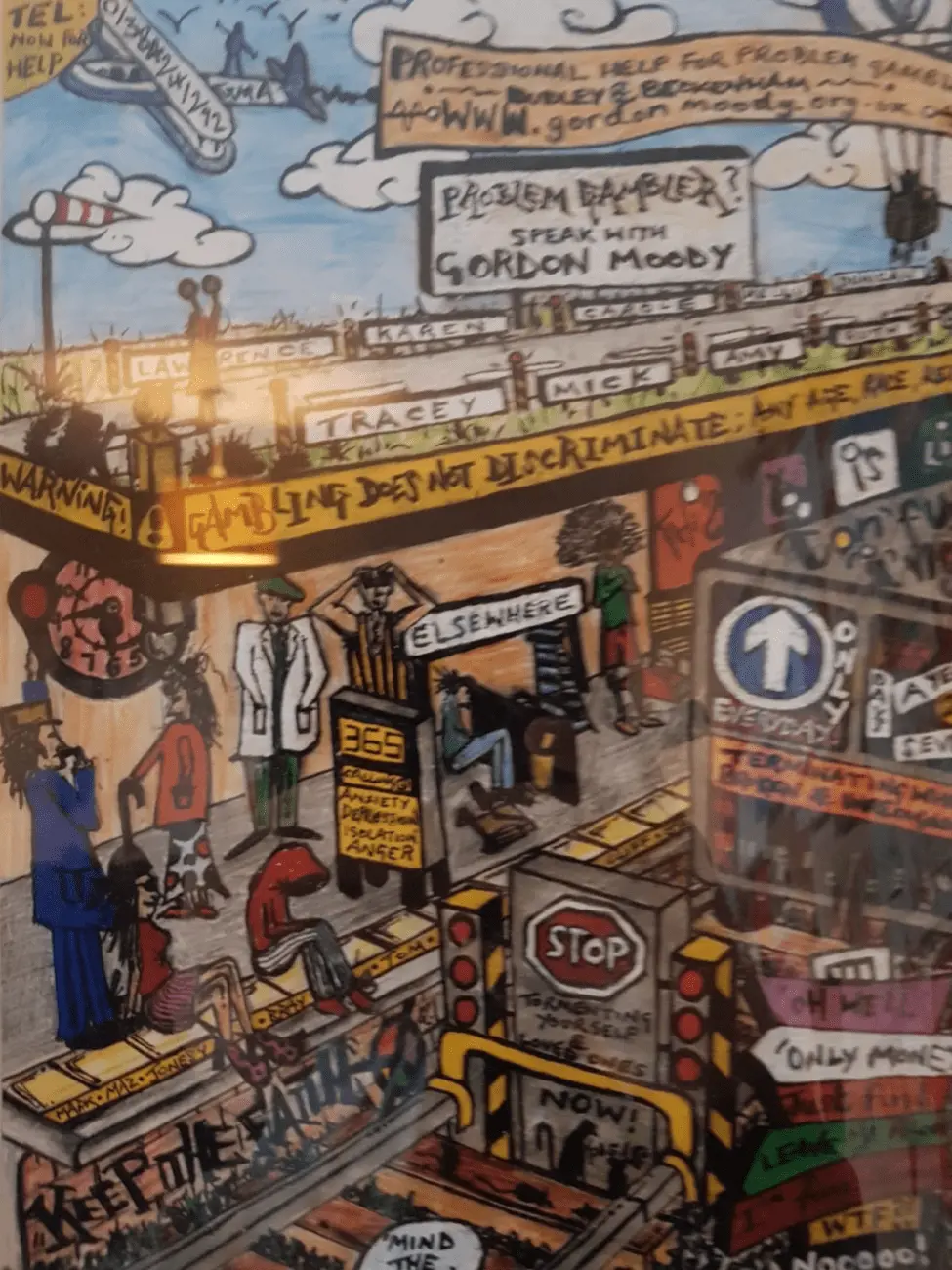

At the back of the garden at 47 Maughan Street in Dudley sits a shelter resembling a football dugout.

At one end, a roadmap interrupted by a series of warning signs: harmful, impending avalanche, corrosive, beware. Along the road are 45 circles, representing losses, and four crosses, representing wins.

At the other is an underground map featuring stops such as “help,” “respect” and — a final stop on one line — “acceptance.”

On the wall in between the two, amid slogans such as “keep the faith” and “out of the darkness” read the names of the staff of the Gordon Moody Residential Centre for gambling addiction.

This artwork doesn’t just have meaning for Stuart Lee of London, the artist who painted the shelter, but for many more of the residents who take part in Gordon Moody’s 14 week gambling rehabilitation programme.

“Most art is personal to the individual, but I wanted to create something that all gamblers could relate to,” Lee said. “Gordon Moody were very happy for me to help out in this way Everyone that comes in here always comments on how real it is and that’s what I wanted. There’s no point in making something that’s aesthetically pleasing that doesn’t really mean anything.”

Lee’s own journey into problem gambling came out of a dark period of his life. After breaking free of a drug addiction, online roulette and blackjack took hold instead, leading to losses of as much as £10,000 in a matter of hours.

“I’ve gambled since I was 15, when I first looked old enough to get into a bookmaker’s,” Lee said. “When I was 25, my girlfriend at the time had an ectopic pregnancy that led me into all sorts, including cocaine. I got out of rehab for cocaine, I was back to me again, but I still needed a distraction from my life and I ended up disappearing into the gambling.”

Eventually, however, Lee had a realisation that his gambling addiction needed to come to an end somehow.

"I texted my brother and my mum and dad and said ‘I’ve had enough’ and switched my phone off for three hours. I just couldn’t do it to them anymore," he said.

After receiving that text, Lee’s brother looked for a solution and found the Gordon Moody Association.

“This place is amazing,” Lee said. “I can’t speak highly enough of this place, I try to do that with my art but it’s really hard to articulate how grateful I am.”

The centre is run by the Gordon Moody Assocation, a charity who have provided residential support and treatment for people who are severely addicted to gambling since 1971. The charity, named after a Methodist minister who set up the first Gamblers Anonymous in the UK, operates treatment centres — the only treatment centres in the UK specifically for gambling addiction — in both Dudley and Beckenham, South London.

The charity is funded mainly through GambleAware, which receives funding from the industry itself and works in partnership with many other gambling treatment services and charities such as GamCare.

“Winning was the worst thing that could have happened” For Tom Chorlton, also from London, the path into gambling was a different one, but the way out again involved family guiding him towards the Gordon Moody Association, this time after a friend of his mother sent her a link to its website.

“My gambling really started at about 8-10 years old when I would go to the Isle of Wight with my family and play the arcades,” Chorlton said. “But I didn’t actually go into the bookies until I was 24 or 25 years old but things got really bad from there. My whole life started falling apart.”

Chorlton’s addiction was to a single game on a fixed odds betting terminal (FOBT) at a single operator’s shops, but left him homeless as his pay packets went directly to fuelling his addiction.

“I had a few wins at the same game when I first started and from there it just exploded. I believed they were just easy money,” Chorlton said. “The first time I played I made about £1000 in ten minutes and I thought, ‘Why am I working? I can just do this and I’ll be sorted’. Winning like that was the worst thing that could have happened to me. It reinforced the idea that I can win and it takes a long time to get past that. Now whenever bills come up and stress comes up it can still be difficult, I have to remind myself that gambling’s not easy money, it’s the opposite, it makes things worse.”

“I’m so grateful for GMA. I’m so thankful that someone gave my mum a link to the website I knew things were bad. I was in a really bad situation. I was working full-time but I was homeless. When I got paid, I just used it all for gambling. I wasn’t able to deal with my own situation and I knew I needed something bigger than a quick fix.”

Lee and Chorlton, like all Gordon Moody residents, first went through a two-week “life audit,” to assess their suitability for the programme, followed by 12 more weeks of rehabilitation including one-on-one and group therapy, each with a focus on a different area of recovery.

When the program ends, ex-residents can continue to benefit from the centre's support. For Chorlton, who continues to live in Dudley but returns to London every weekend, that made a significant difference in returning to the outside world.

“Now whenever bills come up and stress comes up it can still be difficult, I have to remind myself that gambling’s not easy money, it’s the opposite, it makes things worse,” Chorlton said. “But Gordon Moody have been great for support because, living just down the road, I can just drop in and say ‘Can I just have a talk?’”

Lee’s continued connection to the Association, meanwhile, prompted him to volunteer his artistic skills at the residential centre after he completed the programme in 2018. As well as painting the outdoor shelter, Lee built a bed for the centre's cat, Pudding. Like Chorlton, Lee said he has found that spending time around other residents and staff helps him remain on the right path.

“The integration to society after being shut off was very difficult, but you’ve got the support of others and they know how it is,” Lee said. “It’s so good to be around people who have done this programme. The staff here, they’re not just therapists, they’re almost family with that love they have.”

Safety nets While Lee and Chorlton have given up gambling for good, operators, lawmakers and regulators differ on how best to prevent more gamblers from developing similar addictions. Earlier this month, the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on Gambling-Related Harm issued a series of recommendations for the industry, including a £2 stake limit for online casino games, which GVC chief executive Kenny Alexander branded “ridiculous. "

Lee and Chorlton, however, greeted the recommendation positively.

“That would be excellent,” Lee said. “My immediate thought when they said they were bringing it down on the FOBTs was that people can still play online and lose a lot of money online. You could bet even more than £100 per spin.

“Some people will say you’re opening the door for illegal gambling. But illegal gambling will really only appeal to certain people. I think this will still stop a lot of people from losing a lot more money. I think the rule is good news to hear. They need more restrictions. And it makes sense really, it’s not in the gambling companies’ interests to be overly responsible because then their business doesn’t work.”

Chrolton expressed a similar sentiment, believing that no measure could be perfect, but anything that would slow a potential problem gambler down enough to rethink their decisions would help.

“I don’t know if it would have stopped me or if it just would have been the same thing over a slow period of time or with a different game,” Chorlton said of the FOBT stake limit reduction. “It’s always good to try new things to dissuade people, there’ll be lots of trial and error in working out what the best way to make gambling safer is but just having things in place stops me from thinking gambling’s an option. That’s what I need, safety nets. For every three it doesn’t stop, maybe there's seven it does”

Chorlton added that he no longer blames the industry for his addiction, but still believes that advertising messages could be improved to increase awareness of the full effect of responsible gambling.

“I used to blame the companies for all the advertising and making everything so readily available, but with a bit of hindsight I can take more responsibility for my own actions” Chorlton said. “It’s my choices the situations I put myself in”

“The advertising about gambling should be more hard-hitting about the real damage it does though. Like smoking and drunk driving, because the consequences really are equally as bad. I think they’re too jokey and jovial right now about it.”

Lee, however, remains skeptical of the industry’s motives in bringing in changes to promote safer gambling.

“For people who have severe problems but want to exclude, I think the exclusion processes are far too weak,” Lee said. “I sometimes wonder if they make them weaker than they should, knowing that the problem gambler is your meat and gravy, they give you the big money and they’ll find a way around restrictions because that’s the state of mind they’re in. It’s almost like they know a proper problem gambler will always find a way around these restrictions.”

An affirmation As his gambling addiction gets more distant, Lee - who has exhibited his art at a show in London - says any flashbacks to his past only serve to reaffirm how important his recovery is.

“It was hard work, but thankfully I’ve never really had the thought to gamble again,” Lee said. “I do have nightmares, but to me that’s like my subconscious is imagining what it’s like to relapse again. It’s an affirmation not to gamble again.”

To Chorlton, the recovery process never ends, but he said he will always be grateful to have the stability in is life restored.

“It’s forever ongoing,” Chorlton said. “Being here is what’s needed. At first, left to my own devices I would never have the strength to make the right choice. So being here, restricting the movement of money and things was so important. It’s only in the last couple of years I realised that I have a steady job, my own flat, a steady relationship and my family relationships are back in a great spot again. That’s the biggest prize for me. Sometimes the day-to-day of working can seem boring but actually I have loads of good things.”

“You can never take your foot off the gas, you’re only ever one bad decision from being in the wrong place, but if you do make a bad decision you have to remember not to make it worse and you can still come back.”